About a month ago, I took a 2 week vacation trip to China.

One question I wanted to answer for myself during the trip was “how good is the Chinese government?”

I think that learning about how other countries organize their societies and governments is valuable to do when traveling. Especially when, like me, you are an American who is proud of the American way, and deeply baffled that other countries get along any differently than the US.

I think it’s especially valuable in China because it’s a communist (1) country of over a billion people that is American’s biggest political rival. And China also gets lot of very biased coverage in the US (especially along the lines of “the Chinese Communist Party is evil”) so I was excited to see what things looked like for myself. Here’s what I learned! (2)

—

There are two big glaring facts about China that have to form the backdrop of understanding “is the government good?”:

On this second point, government satisfaction is definitely inflated a bit by propaganda. But it’s hard to underestimate how much better things have gotten in China over the lifetime of many of its citizens.

I think that’s uncontroversial so I won’t go through too many stats to belabor the point. Here’s just one: The share of people living in extreme poverty went from 70% to under 1% over the past 30 years.

More qualitatively, here’s what I saw when traveling: Cities are clean. The infrastructure for things like electricity, transportation, internet, education are all quite good. Food and clothes are very cheap. It is so easy to rent a bike to ride around Shanghai and Beijing.

On most of the things that affect your day to day life - the concrete things that make a difference in your day to day happiness - the Chinese government has done a great job. A greater job in a shorter period of time than any government in history.

But there are issues. To my mind there are three big ones:

People can just be disappeared. One friend in China told a story about how a coworker of his had been linked to protests happening in China last year, and she simply disappeared from work. She had been arrested, no telling when she would be let out. After a few months she appeared back for a week or two - and did not want to talk about what happened - before disappearing again.

There’s not much you can say in defense of this.

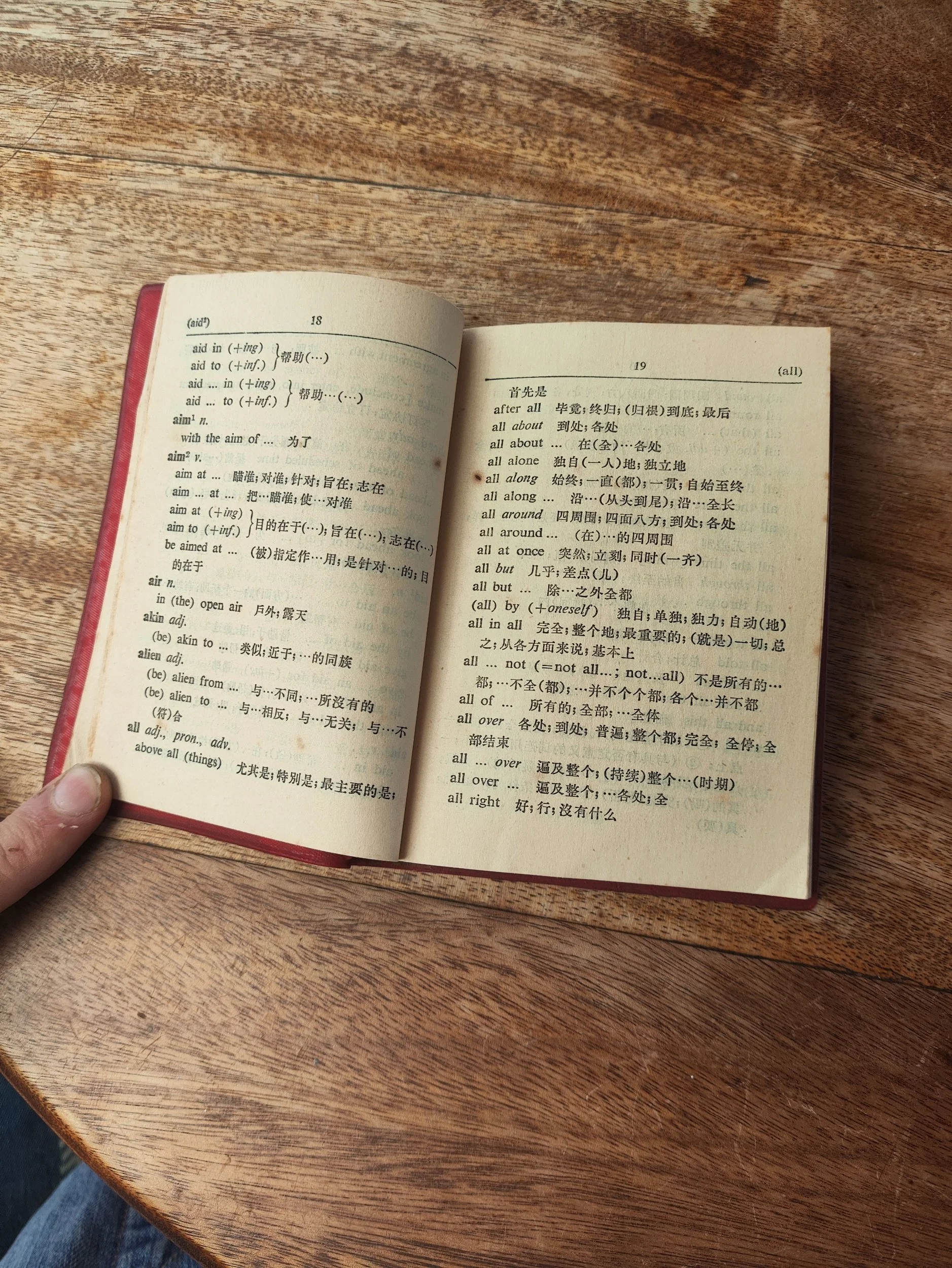

People cannot access information. The internet is entirely censored. You can’t learn about things like the Tianamen Square massacre or the A4 movement. You can’t use Google products. You can’t use ChatGPT.

Now you can get around these with a VPN, but it takes a little bit of work. Two thirds of people don’t bother (3).

Religions are oppressed. The CCP tries to control religious organizations - such as the Catholic Church and Tibetan Budhists - by appointing religious leaders itself. If you are in certain government jobs and are religious, you have to be quiet about your faith (4). And of course there are the terrible things going on against Muslim Uighers in Xinjiang.

—

These issues are super important in terms of the American ideal of civil liberties. But they are relatively small in terms of how they affect most peoples lives day to day. You might argue - as many Chinese do - that they are worth trading off for the more tangible life improvements people have gotten (5).

Ultimately I think this idea of “trading off” civil liberties for material comfort is a false dichotomy. You can have both material success and not have to worry about vanishing for having unpopular political opinions. The CCP perpetuates the idea that it is a tradeoff to justify its hold on power.

So I don’t want to minimize the terrible things that happen in China. But they are definitely overemphasized in American media coverage of China. And it’s not like the US has a spotless record on civil liberties.

So overall is Chinese government good? Overall my answer is “it’s ok.” I definitely think the “China is evil, US is not” framing in popular discourse is unhelpful (6)

—

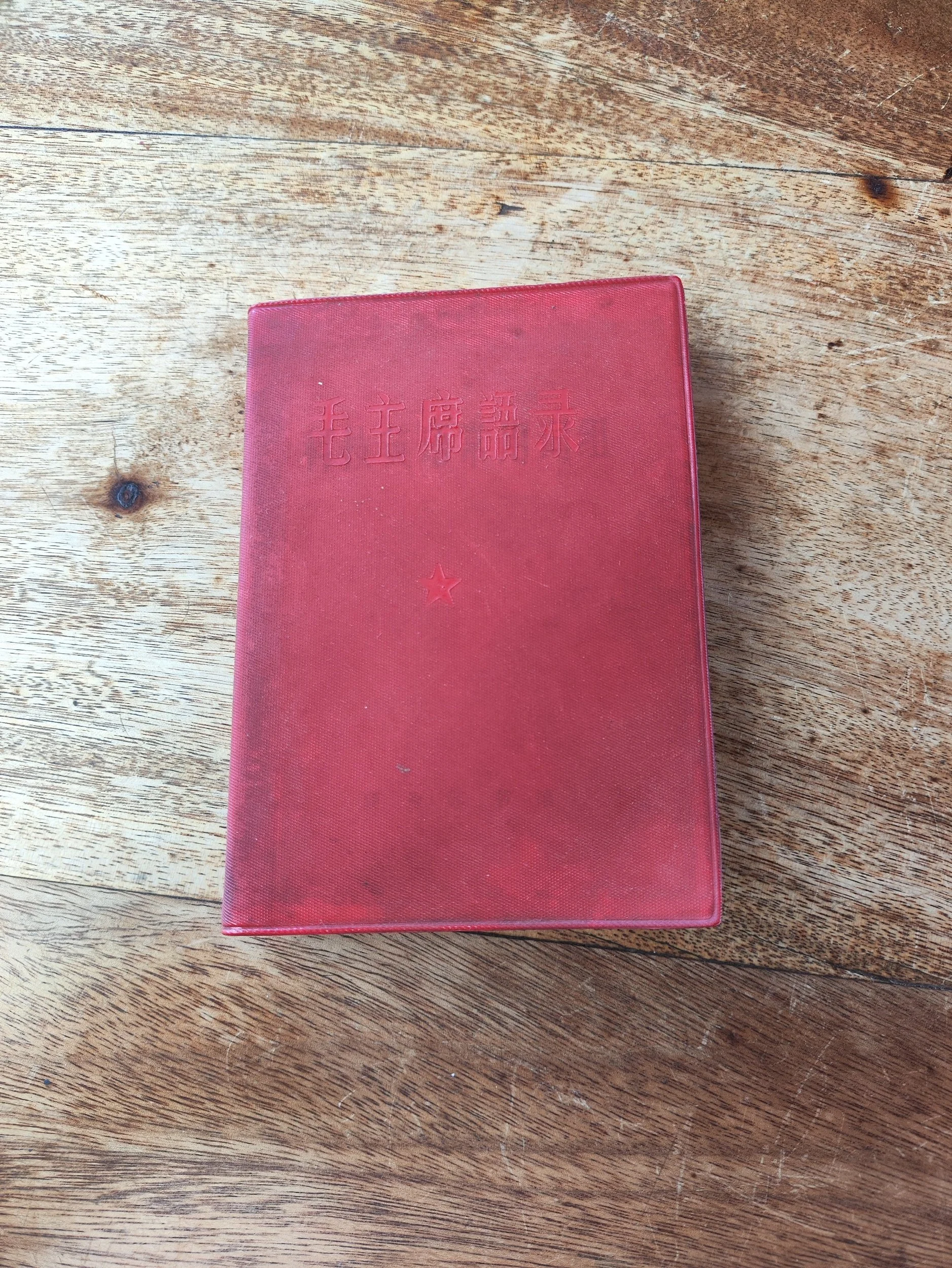

Well, you know, at least it has communist characteristics

Caveat that obviously “How good is the Chinese government?” is a super big and complex question, and of course I do not have a definitive answer. I think for people interested in how humans organize themselves, it’s useful to have a “working theory” for questions like this. These are views I’ve thought a lot about over the past few years and built up mostly from discussions with friends, reading a few books, and taking this two week trip, but I am nothing like an expert on political theory or Chinese politics.

Sometimes people make arguments to the effect that the media landscape in the US is not just as biased - even if we have access to information in theory, what we actually get is biased by the interests of small groups of people. I agree this is a big problem (and this is something I have changed my view on within the past year or so). But state control in China is way worse.

It’s not like I ever felt in danger or anything being there. When it came up, people were very respectful of my faith. My girlfriend’s dad even found it important to explain to extended family that there were important distinctions between Catholics and Protestants - alas that it was in Mandarin and I could not understand

One friend I talked to said that the younger generation - especially those educated abroad - care more about civil liberties. Whereas their parents - growing up in the Cultural Revolution and seeing how bad things can be as well as how much better things have gotten since then - tend to not worry about rights and are more grateful for the concrete improvements that have happened

Here is an example of what I mean by that: In discussions about how the US should approach AI regulation, people sometimes make an argument like “The US has to stay ahead of China. Even if moving fast leads to some bad outcomes, those outcomes won’t be as bad as if China is ahead.” I think this argument uses a caricature of “big evil China” to argue for something reckless.

After my trip I’m also much more open to