“A story is a way to say something that can't be said any other way, and it takes every word in a story to say what the meaning is. You tell a story because a statement would be inadequate.” – Flannery O’Connor

“Oh dip” – Jason Mendoza

“What does it mean for art to mean something? How should we try to understand art? What makes a piece of art good? What is even the point of art? These are all big thorny questions that 1. Are not directly addressed in but are at the core of today’s blog post 2. I think I have the answers to, and 3. May be the subject of future blog posts” - Luke Eure

Trying to understand what arguments a work of art is an exercise I find very fun and insightful (“work of art” is a phrase which here means “basically any creative endeavor, ranging from NBC sitcoms, to haikus you wrote while bored in freshman bio, to philosophical sci-fi novels”). Some works of art make very clear arguments (Atlas Shrugged has a character give a 50+ page monologue where he tells you what the books is about). Some can be interpreted as making any number of arguments, many in direct contradiction to each other (talk to anybody about Parasite or try to untangle what Kanye’s message is in Gold Digger). And some works of art are more interested in raising questions or exploring emotions than in articulating specific arguments about those questions (e.g., Whiplash: Is the self-destructive pursuit of excellence worth it?).

So it’s not always the case that a work of art clearly makes a certain moral argument (i.e. a piece of art isn’t always telling you to act or feel a certain way). And even if it is making an argument, it’s not likely that you can exactly reproduce the argument with all its subtlety in words, because if you could then the piece of art would just be a philosophical argument and wouldn’t be interesting at all as a work of art. But trying to articulate all the different moral arguments a piece of art could be making is one fun and useful way to approach interpreting art, and one that can lead to understanding.

In this week and next week’s blog posts I’d like start to try to analyze what kind of arguments are made in NBC’s The Good Place. Take as a whole, what do the four seasons of the show tell us about how we ought to live our lives?

Disclaimer: I’m not an art critic or a serious philosopher, and don’t know that much about TV or art criticism or the nuanced history of philosophy. Lots of very smart critics and philosophers have written about this show I’m sure, but I don’t know who any of them are and haven’t read any of their work. But I like to think critically about things, and have read a good number of New Yorker articles in my time. And I have a blog which you’re inexplicably reading, so here we go.

There are 3 big moral arguments that The Good Place makes that I’d like to explore in this post. I will tackle a few more arguments in next week’s post, because the length of this post is already getting out of hand and I haven’t even started on the arguments.

1. A meta-argument: Morality is important and worth talking about

2. An argument for existentialism: Morality is what you make of it

3. An argument for moral realism: “Justice” as a concept really exists

Argument #1: Morality is important and worth talking about

Any work of art can be said to be making at least one argument about its subject matter, and that is “this thing is important! Important enough that I’m making art about it!” In Little Women when Jo March writes a book about domestic matters, she’s implicitly saying that these domestic matters are important enough to write and be read about. The fact that the world is full of love songs can be interpreted as an argument that love is really important and ought to occupy roughly half of our singing time.

Similarly, when Michael Schur makes a TV show about moral philosophy, he’s saying that moral philosophy is important. And when that show is on NBC during primetime, and stars Kristen Bell and Ted Danson, and is designed to be broadly appealing, then that show’s existence is an argument that moral philosophy is important for everybody. Everybody, not just academics and pretentious teenagers, should be thinking about what it means to be a good person.

Argument # 2: Existentialism -- Morality is what you make of it (this is where the spoilers start)

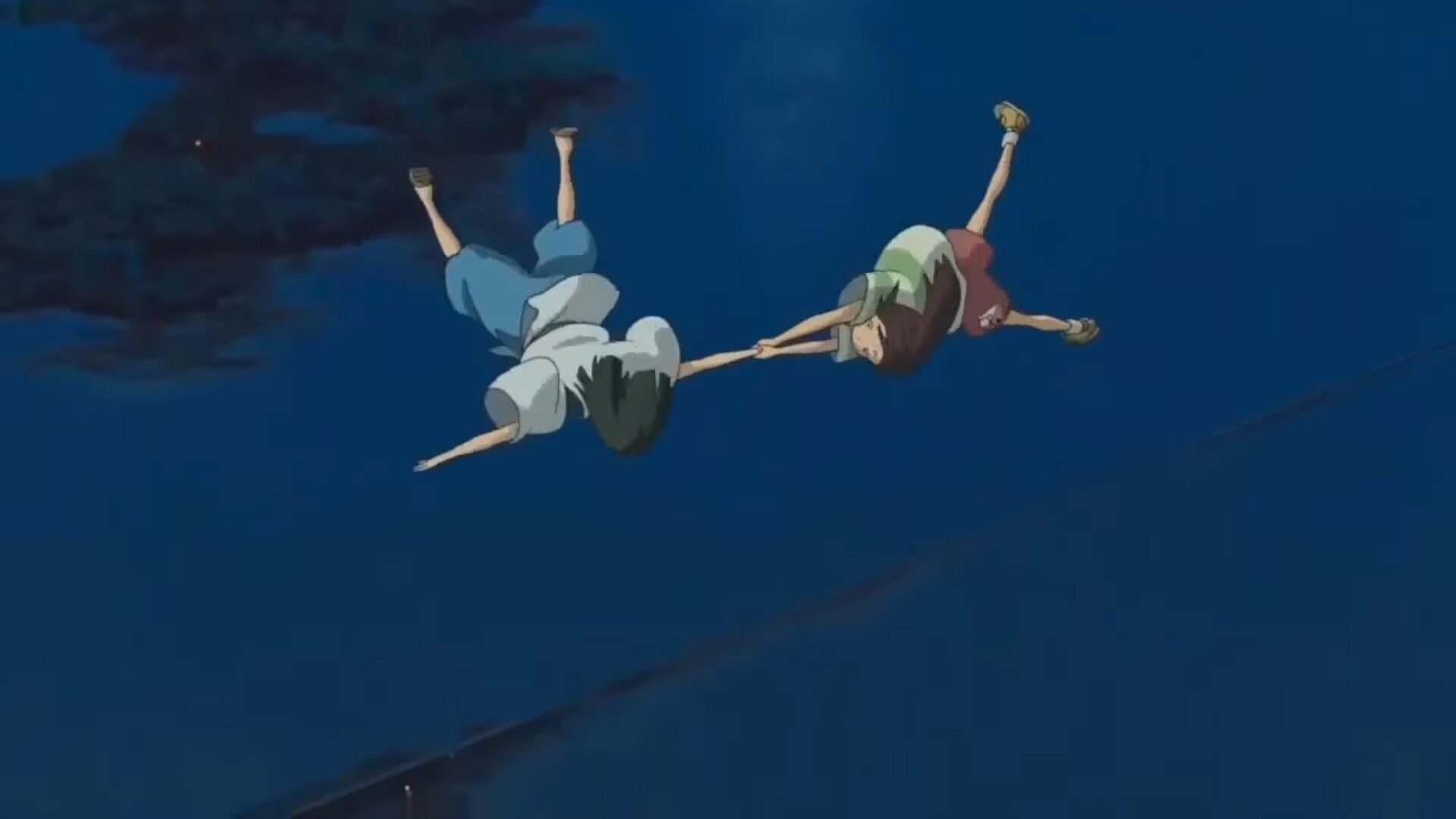

My one-sentence summary of the plot of The Good Place is: “Some people and their demon friend discover that the universe’s system of morality is broken, and design their own system to replace it.” When confronted with a system of morality (the points system) that doesn’t reward and punish people the way our main characters think it ought to (because it sends everyone to the Bad Place), they take it upon themselves to reject this system of morality and replace it with their own (people are allowed to try and try again to improve themselves until they are good). The idea that morality is not fixed and each person must seek for themselves what is good and meaningful is a core idea in existentialism.

The Good Place rewards our main character for replacing the established moral system with their own version of morality. During the course of the show, we see that our main characters question the real metaphysical rules that govern the Good Place and the Bad Place – rules that have been in place for as long as humans have been giving rocks to each other and killing each other with those rocks. Our heroes come up with a version of morality that makes more sense to them than the established system, and then are rewarded for following their intuition about how morality should work over the established rules. If someone like Chidi comes along with an idea of what the rules of morality should be, then it’s fine for the whole universe’s system of morality to change in response. Morality is not a given, but can be molded to fix the preferences of those it affects.

If I’m to follow Chidi’s example, I should live my life searching for the version of morality that gives my life meaning and that makes sense to me and that will make me and the people I love happy. And then I should use that as my moral code. Moral codes are arbitrary and can be changed if they don’t work anymore – what’s important is my own interpretation of how the universe ought to work in this time and place.

Argument # 3: Moral realism – “Justice” as a concept really exists

“But wait”, you might say. “The self-improvement-simulation system of morality that we end up with in Season 4 of The Good Place isn’t depicted as being an improvement on the points system just because our main characters like it better than the old system. It’s really a more just system. The whole reason Michael convinces the Judge to replace the old system is because everyone can see that the existing points system is not a good system.” But this doesn’t make sense if we think that morality at its base really consists of the points system as enforced by the Judge. Because how can the ultimate moral system of the universe be “not good”? The “good” thing to do is defined as “the moral” thing to do. So in order for the points system to be a bad system, it must not be the true underlying morality that governs the universe.

The show can reasonably be interpreted under the view that there exists a fundamental moral law that exists at a higher level than the points system. This law escapes all of the main characters. None of the supernatural beings -- not the basic Judge, the petty Demons nor the ineffectual Good Place Committee -- really have a full grasp on what the rules of this fundamental morality are. But they can tell that something is going wrong when their point system is sending everyone to the Bad Place, really truly wrong and unjust. So they create a new system with the help of some humans. It’s clear that the self-improvement-simulation system that they create is more just than the points system, and the fact that everyone agrees that it’s more just is an indication that there exists some external sense of “justice” that they are measuring against.

If interpreted as arguing for moral realism in this way, then the message The Good Place to us is that we ought not to accept rules of morality or societal structures that are handed to us if they are unjust. We should search for what is truly good, and pursue that.

These are just three of the moral arguments that you can interpret The Good Place as making. Since I’m already way longer than any of my blog posts have been so far, I’m going to stop here for this week, and pick up next week with a few more moral arguments made by the show.